Occupational Exposure Assessment is the practical process of figuring out who is exposed to what, how much, how often, and whether controls are working—before health problems show up.

It sits at the core of occupational hygiene because it turns “we think it’s fine” into evidence-based decisions, using professional judgment, exposure profiles, and (when needed) sampling.

- Occupational Exposure Assessment in plain language

- Build Similar Exposure Groups (SEGs) that actually work

- Create an “exposure profile” before you touch a pump

- Choose the right benchmark: OELs and “not a bright line”

- Sampling basics: decide what question you’re answering

- Turn results into decisions, not just numbers

- Records that stand up: what to document every time

- Make it sustainable: review triggers and continuous improvement

- A short example to tie it together

Occupational Exposure Assessment in plain language

Occupational Exposure Assessment is not only “air testing.” A strong program starts with understanding tasks, materials, and controls, then deciding what you can confidently conclude and what needs more information. AIHA notes that monitoring is not always essential to exposure assessment and that you can often assess exposures using a blend of qualitative judgment, modeling, and targeted measurements when uncertainty is high.

That mindset is important for busy workplaces. If you treat sampling as the first step, you’ll waste money testing the wrong people on the wrong day, then struggle to interpret results.

If you treat assessment as a structured decision process, you can prioritize the biggest health risks quickly and use sampling as a verification tool—not a fishing expedition.

Build Similar Exposure Groups (SEGs) that actually work

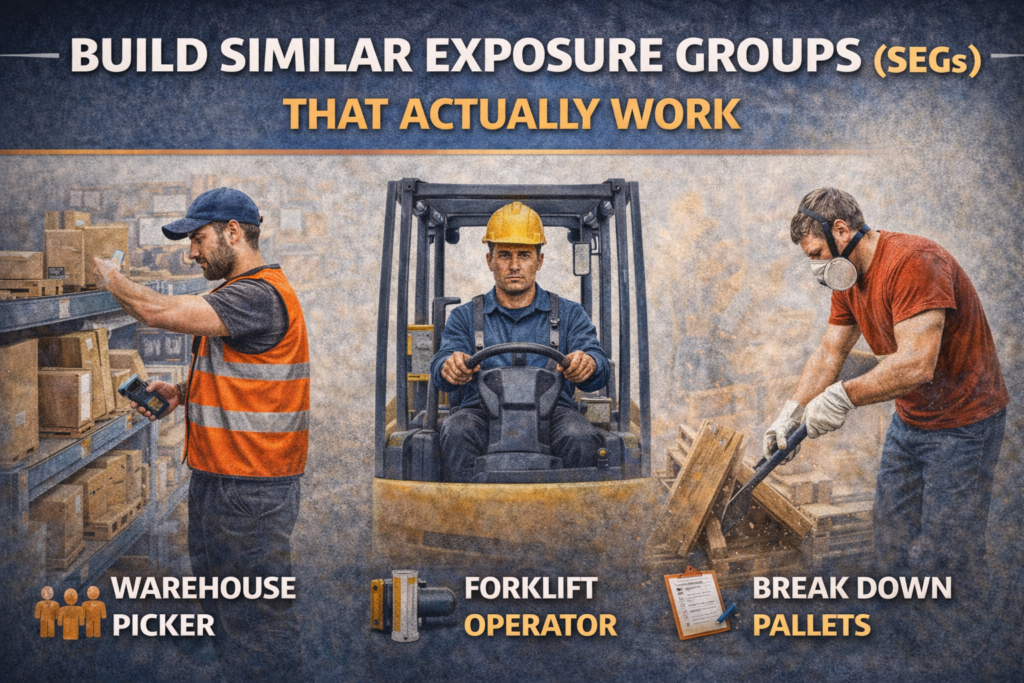

A Similar Exposure Group (SEG) is a group of workers who have similar exposure profiles because they do similar tasks, with similar materials, controls, and time patterns.

This is how you scale an assessment without pretending every worker is identical. AIHA training materials outline grouping workers into SEGs, defining an exposure profile for each group, and judging whether that profile is acceptable.

To build a usable SEG, avoid job titles alone. “Warehouse Associate” can hide major differences: one person picks small cartons at chest height; another breaks down pallets at floor level; another drives a forklift near diesel exhaust. Instead, define SEGs by:

- Task patterns (what is done, how often, for how long)

- Agent types (dust, solvent vapours, welding fume, noise, etc.)

- Controls (local exhaust, wet methods, enclosures, respirators)

- Environment (indoors/outdoors, temperature, ventilation, peak-season pace)

In Ontario, guidance for designated substances explains that employers may determine personal exposures by assigning workers to an exposure category where similar conditions of exposure exist (instead of monitoring every worker). That principle is exactly what SEGs are built for.

Create an “exposure profile” before you touch a pump

Occupational Exposure Assessment gets easier when you write a simple exposure profile for each SEG. Think of it as a one-page “story” of exposure that includes:

- agents present and why they’re present

- likely routes (inhalation, skin, ingestion)

- when exposure spikes (startup, cleaning, changeovers, peak shipping)

- current controls and how reliable they are

- what could go wrong (failed ventilation, open lids, rushed pace)

This is where you decide whether your best next move is control improvement or data collection. If controls are obviously weak (for example, dry sweeping visible dust every day), you can often act immediately and then sample later to confirm the improvement.

Choose the right benchmark: OELs and “not a bright line”

You need a benchmark to judge acceptability. In practice, that’s often an occupational exposure limit (OEL) for airborne hazards (and sometimes surface limits or biological monitoring benchmarks).

CCOHS emphasizes that an OEL should not be treated as a sharp line between “safe” and “unsafe,” and that exposures should be reduced as much as possible, especially for certain higher-risk agents.

This matters in the real world because two workplaces can both be “below the limit” while one has frequent peaks, poor control reliability, and worker complaints. Your exposure profile should consider:

- time-weighted averages versus short high peaks

- uncertainty (limited data, changing processes, seasonal ventilation)

- severity (sensitizers, carcinogens, acute irritants)

Sampling basics: decide what question you’re answering

When you do sample, be clear on the question:

- Worst-case check: will any worker exceed the benchmark during high-exposure tasks?

- Typical exposure estimate: what is the normal range for this SEG over time?

- Control verification: did a change (LEV repair, enclosure, product swap) reduce exposure?

Different questions lead to different sampling choices. Government sampling guidance in Canada references using the NIOSH Occupational Exposure Sampling Strategy Manual approaches for decision-making near OELs, including confidence bounds concepts for interpreting results.

Personal vs area sampling (and why personal matters most)

For inhalation risk, personal sampling in the breathing zone is usually the most useful because it represents what the worker actually experiences.

Area samples can help map sources, evaluate ventilation, or screen for problems, but they don’t replace personal exposure estimates for SEG decisions.

Full-shift vs task-based sampling

Full-shift sampling supports TWA-style benchmarks. Task-based sampling is powerful when exposure happens in bursts (mixing, sanding, filter changes). If there’s a ceiling or short-term limit concept for the agent, short-duration sampling becomes critical.

CCOHS summarizes common limit types like 8-hour averages and short-term limits and why short spikes can matter even when an 8-hour average is lower.

How many samples do you need?

There’s no single magic number, but you do want enough data to reduce uncertainty. A practical approach is:

- start with a few well-chosen samples that represent the highest and most typical conditions

- if results are close to the benchmark or conditions vary a lot, collect more across days/shifts/seasons

- if results are clearly low and controls are stable, shift to periodic verification

The key is consistency: Canada’s sampling guidance stresses that strategy and conditions should be consistent so results can be compared over time.

Turn results into decisions, not just numbers

Occupational Exposure Assessment is successful when results lead to clear decisions for each SEG, such as:

- Unacceptable: fix controls now, then resample to confirm improvement

- Acceptable: keep controls, schedule periodic verification, and watch for change triggers

- Uncertain: gather more information (better task definition, more sampling, modeling, or biological monitoring)

A useful habit is to document what would change your decision. For example: “If production increases by 20%,” “If we switch to a higher-volatility solvent,” or “If the local exhaust fails a smoke test,” then the SEG needs reassessment.

Records that stand up: what to document every time

Good records protect workers and help the employer prove due diligence. Ontario guidance on air monitoring and exposure records for designated substances describes maintaining records of personal exposures and capturing things like monitoring results, calculated time-weighted averages, ranges by exposure category, and trend indications.

Also, in the U.S., OSHA’s access rule highlights that employees have a right of access to relevant exposure and medical records, reinforcing why records must be organized and retrievable.

Even if you operate in Canada, that principle is still best practice: exposure records should be easy to find, understandable, and usable for future decisions.

Here’s a practical “minimum record set” you can reuse for each SEG (keep it in your OHSE system, not in someone’s inbox):

- SEG definition (who is in, who is out, and why)

- tasks/processes, schedule, and duration assumptions

- agents assessed and benchmarks used (OELs or other criteria)

- controls in place (engineering, admin, PPE) and their reliability

- sampling plan (who/when/where/how, method, lab, calibration notes)

- results summary (including peaks vs averages where relevant)

- decision category (acceptable/unacceptable/uncertain) and rationale

- actions, owners, due dates, and follow-up verification triggers

If you’re building your overall OHSE program framework, you can align this documentation with your broader hazard-control approach (and training expectations) using resources like OHSE.ca’s OHSE overview and certification pathway.

Make it sustainable: review triggers and continuous improvement

A one-time Occupational Exposure Assessment becomes outdated fast. Set simple triggers so reassessment happens automatically:

- process changes (new chemical, higher heat, new equipment)

- volume changes (peak season, extra shifts, overtime)

- ventilation changes (layout, doors kept open/closed, filters clogged)

- worker reports (odours, irritation, headaches, dermatitis, coughing)

- incident signals (spills, leaks, near misses, control failures)

AIHA’s view that exposure assessment blends judgment with tools is helpful here: you don’t need constant sampling, but you do need a living process that updates when risk changes.

A short example to tie it together

Imagine a metal fabrication shop with welding, grinding, and solvent wipe-down. You might create three SEGs: (1) welders, (2) grinders/finishers, (3) painters/wipe-down techs. You’d build exposure profiles (fume, dust, solvents), confirm controls (LEV, general ventilation, product substitution), then decide what sampling is needed.

If grinders are dry grinding without capture, you might act first—add capture or wet methods—then sample to verify reduction. If wipe-down uses a high-volatility solvent, you might sample task peaks and check for skin exposure controls too.

That’s the core idea: define the SEG, describe the profile, choose the right data, document the decision, and improve.

No comments yet