Confined space rescue plans are the last line of defence when something goes wrong inside a tank, vault, pit, or manhole.

Most fatalities in confined spaces happen to would-be rescuers who rush in without a clear procedure, proper gear, or training.

A well-designed plan turns chaos into an organized response that protects workers, bystanders, and emergency services.

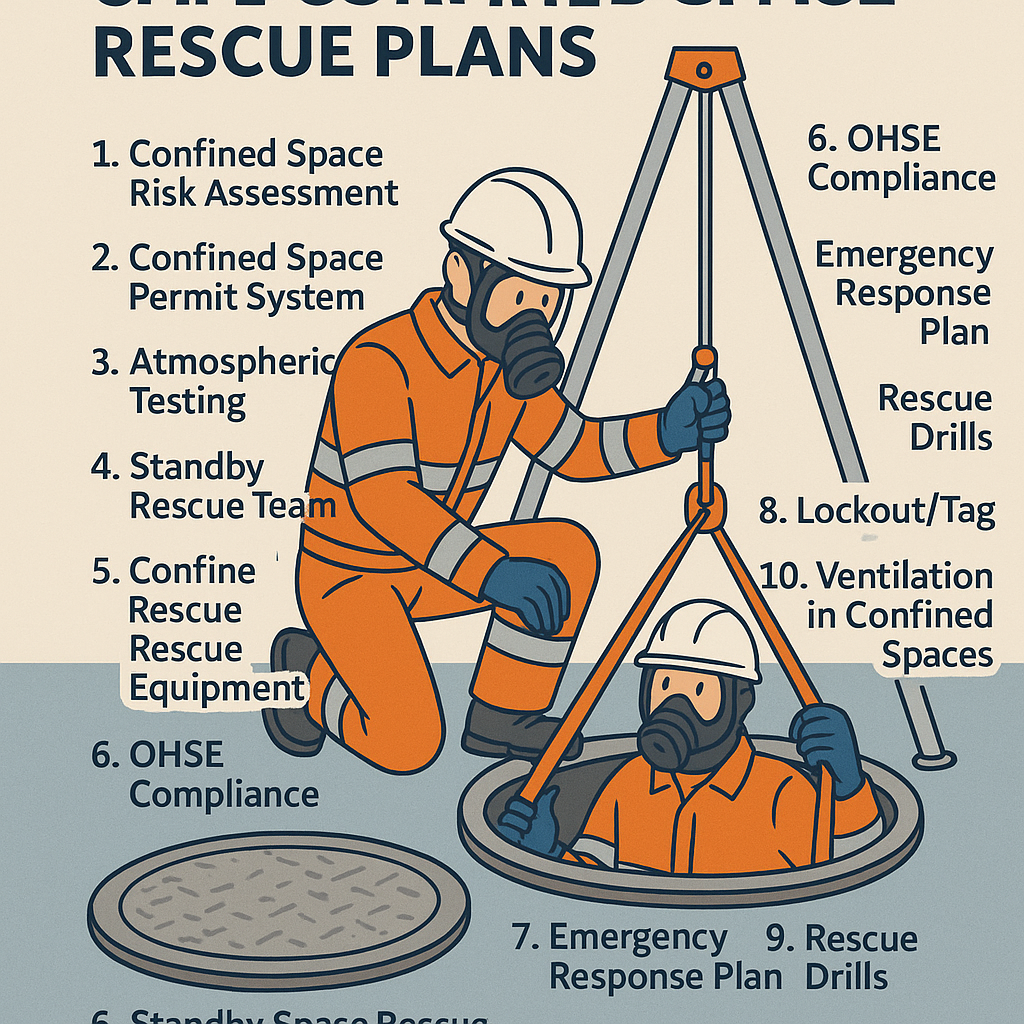

Below are ten critical steps to build or review a confined space rescue plan that actually works in the field, not just on paper.

- 1. Define where your confined space rescue plans apply

- 2. Identify credible rescue scenarios, not just “worst case”

- 3. Decide when non-entry rescue is mandatory

- 4. Plan for entry rescue only where absolutely necessary

- 5. Assign clear roles and competencies

- 6. Specify rescue equipment in detail

- 7. Integrate atmospheric monitoring and ventilation into the plan

- 8. Coordinate with external emergency services in advance

- 9. Drill the confined space rescue plan realistically

- 10. Keep documentation simple, accessible, and current

1. Define where your confined space rescue plans apply

Start by clearly identifying every confined space on your site and classifying it as permit-required or non-permit according to your local regulations (for example, the OSHA confined spaces standard or Canadian requirements from CCOHS).

Document typical tasks, contractors involved, and potential rescue limitations (access through a hatch, vertical entry, long horizontal crawl, etc.).

Connect this inventory to your existing confined space entry procedures and permits so the rescue plan is always tied to a specific space, not written as a vague generic document.

2. Identify credible rescue scenarios, not just “worst case”

A strong plan anticipates realistic situations. Consider scenarios such as loss of consciousness from low oxygen, sudden toxic gas release, worker collapse from a medical event, mechanical entrapment, or communication failure.

Look at near-miss reports, JHAs, and your confined space entry checklist to see where things most likely go wrong.

For each scenario, think about where the entrant will be, whether they will be attached to a retrieval line, and how quickly conditions may deteriorate. This drives all other decisions in your confined space rescue plan.

3. Decide when non-entry rescue is mandatory

Industry best practice is simple: if you can safely perform non-entry rescue, you should. That means the entrant is continuously attached to a retrieval system (tripod, davit, or overhead rail) and can be removed without sending anyone else inside. Your plan should specify:

- Which spaces require pre-rigged retrieval systems

- Approved anchorage points and equipment

- Who is authorized to operate the winch or SRL

Make it clear that non-entry rescue is the first choice whenever it is feasible and does not create additional hazards to the entrant or rescuer.

4. Plan for entry rescue only where absolutely necessary

Some spaces simply do not allow non-entry rescue—long piping runs, complex vessels, or spaces with internal obstructions. In those cases, your confined space rescue plans must define how an entry rescue will be performed:

- Minimum number of rescuers for safe entry and back-up

- Atmospheric control requirements before and during rescue

- Acceptable time window for entry vs. waiting for external fire/EMS support

Your plan should explicitly prohibit “impulsive rescue” by co-workers who are not part of the designated rescue team.

5. Assign clear roles and competencies

Every rescue plan should name roles, not just tasks. Typical roles include Entry Rescuer, Non-Entry Rescuer/Winch Operator, Rescue Team Leader, Attendant, and Incident Commander (often a supervisor). For each role, define:

- Required confined space and rescue training

- Fitness and medical clearance expectations

- Authority to stop work or deny entry

These role descriptions should align with your broader emergency response and OHSE responsibilities so that people are not receiving conflicting instructions in an emergency.

6. Specify rescue equipment in detail

Vague phrases like “rescue equipment available” are dangerous. Your confined space rescue plan must list exactly what is required for each type of space, for example:

- Tripod or davit system rated for the load

- Self-retracting lifelines with rescue capability

- Full-body harnesses with front and dorsal attachment points

- Atmospheric monitor calibrated for oxygen, flammables, and specific toxic gases

- Ventilation blower with compatible ducting

- Communication equipment (radios, hard-wired intercom, or lifeline signals)

- Patient packaging devices such as a rescue stretcher or SKED

Tie this to a maintenance and inspection schedule so rescuers can trust the gear will function when needed. Resources like NIOSH confined space guidance can help you benchmark equipment expectations.

7. Integrate atmospheric monitoring and ventilation into the plan

Many rescues fail because no one is monitoring the atmosphere once the emergency starts. Your plan should state:

- Who is responsible for continuous air monitoring

- Alarm set-points for oxygen, LEL, and toxic gases

- Actions when alarms trigger (evacuate vs. continue with additional controls)

- Minimum ventilation rates and how ducts must be positioned

Make sure the rescue team understands that “readings were fine at the start” is never a substitute for continuous monitoring inside a confined space rescue plan.

8. Coordinate with external emergency services in advance

Do not assume the local fire department can automatically perform confined space rescue. Many departments lack the specialized equipment or training for complex industrial spaces. Reach out in advance to review:

- Site maps and access points

- Typical confined spaces and hazards

- Where they can connect their equipment

- Communication channels and command structure

Include their limitations in your written procedures.

Some sites maintain in-house rescue capability for high-risk spaces but still rely on EMS for medical stabilization and transport.

9. Drill the confined space rescue plan realistically

A rescue plan that has never been practised is only theory. Schedule regular drills for each representative type of space (vertical, horizontal, narrow entry, inerted, etc.). During drills:

- Use full PPE, retrieval systems, and monitors

- Time the response from alarm to patient removal

- Test communication between entrants, attendants, and supervisors

- Evaluate how documentation and permits are handled under stress

After each drill, hold a debrief, capture lessons learned, and update your procedures. Posting a summary on your internal OHSE portal or linking it to articles such as your lockout/tagout safety guide on OHSE.ca reinforces learning across the organization.

10. Keep documentation simple, accessible, and current

Finally, even the best confined space rescue plans fail if workers cannot find them or understand them. Use concise, visually clear documents that live where the work happens:

- Laminated rescue flowcharts at each high-risk space

- QR codes on entry permits linking to the full procedure on your intranet

- Checklists for attendants and rescue team leaders

- A single emergency contact card with internal numbers and 911 details

Review the rescue plan at least annually, or after any significant change: new equipment, process changes, modified vessel internals, or an incident.

Encourage workers to suggest improvements; they see the practical barriers every day.

A well-designed confined space rescue plan is not just a compliance requirement—it is a commitment that no one will be left behind in a life-threatening situation.

By identifying realistic scenarios, prioritizing non-entry rescue, equipping and training a competent team, and drilling the procedure until it becomes second nature, you turn a high-risk job into a controlled operation.

Investing time now in robust confined space rescue plans can be the difference between a close call and a tragedy.

No comments yet